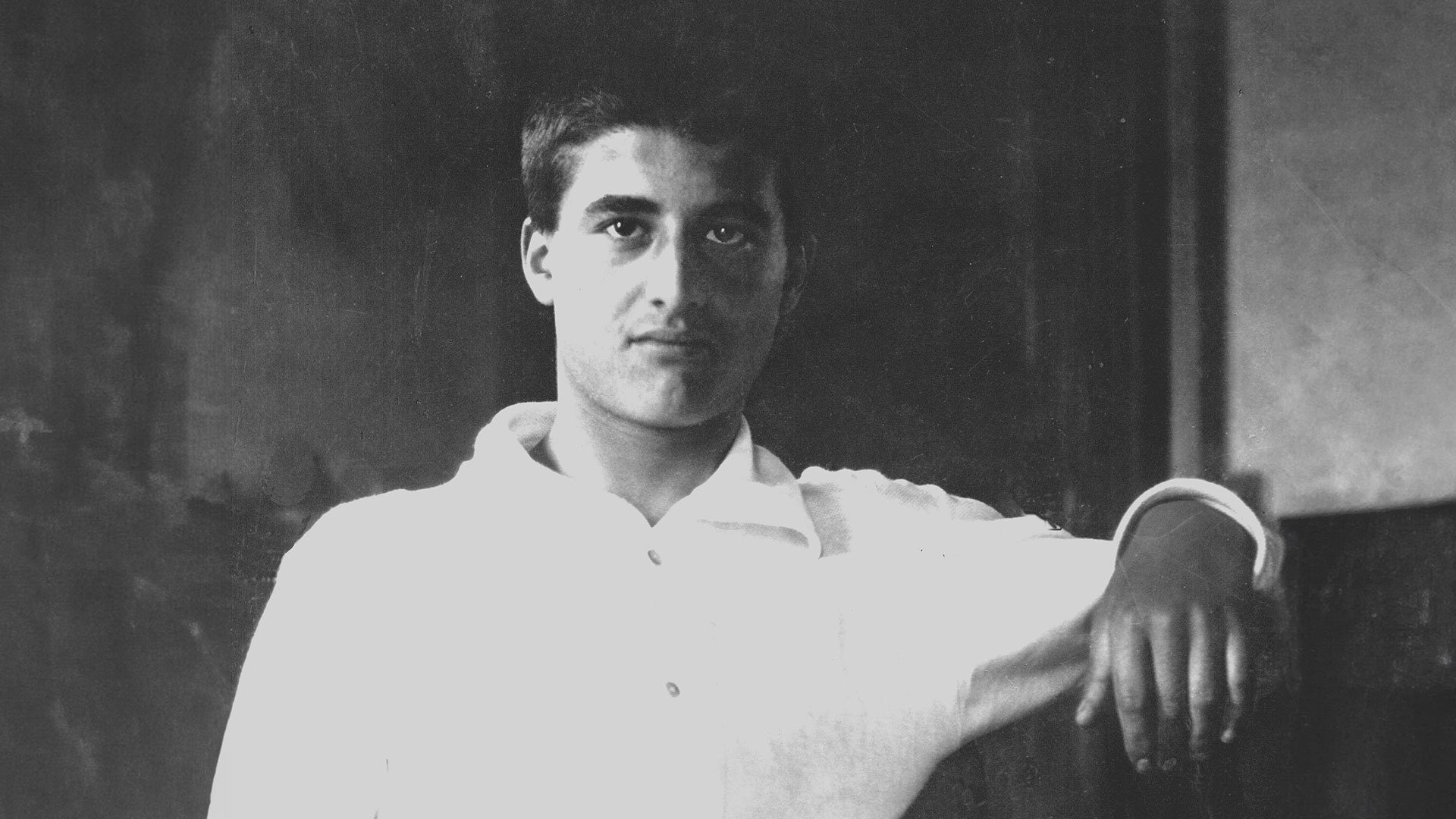

Leonardo Murialdo: A Vision That Transcends

Leonardo Murialdo (1828-1900), canonized by Pope Paul VI in 1970, could have embarked on a brilliant public career due to the privileged status of his family. However, he chose a different path. His youth was spent during a time marked by tensions that swept through Europe after the Congress of Vienna, caught between aspirations for freedom and harsh repressive policies. In his spiritual testament, Leonardo openly discusses a period of turmoil during which he fell into the “abyss of sin.” Overcoming his youthful crisis by the grace of God, he dedicated himself to studying philosophy and theology in Turin, and became a priest in 1851.

From the beginning, his focus and efforts, supported by the great Saint John Bosco, were directed towards prisoners, young workers, and generally youths in difficulty, thus manifesting the ‘social’ vocation of his apostolate. Leonardo was uncompromising. The nascent industrialization in 19th-century Turin created discomfort and stark social contrasts, and he believed that the Gospel’s message could not be reduced to comforting formulas; it had to inspire guidelines and solutions. Leonardo did not hesitate to incur debts, which haunted him until the end of his life, to initiate projects ranging from the foundation of a college called “degli Artigianelli” to house orphaned boys for work, to opening institutions for former prisoners, agricultural colonies, and housing for homeless youths. A devotee of Saint Joseph, he also founded the Congregation of the “Giuseppini,” which is still active today in Italy and abroad.

His actions were tireless, as was his unwavering trust in Providence. But that was not enough. Leonardo, like Don Bosco, understood that the redemption of the marginalized also involved advocating for their rights in the workplace. He was well-informed about the worker’s condition in Europe and the experiments in this regard in France, England, Germany, Switzerland, etc. He actively participated in the early initiatives of the Catholic Workers’ Unions, advocating for reduced work hours and less burdensome employment conditions for youths.

Leonardo was not one to accommodate, as mentioned, and he even dared to prod his fellow priests to take an interest in the working class condition: “Christian worker and popular associations are still unknown and undervalued by priests, who do not realize that these are today the only indispensable means to prevent the total ruin of faith in the hearts of the people. Engrossed in their studies, immersed in the silence of the sanctuary, almost separated from the world, our priests continue the ancient traditions of piety, holiness, and knowledge; our seminaries peacefully continue to shape virtuous ministers of the altar and, when necessary, brave martyrs. But the worker’s apostolate, so Catholic and so social, remains foreign to them.”

Similarly, looking beyond his century, he encouraged Catholics with the ability to personally utilize the media: “The Catholic who possesses the qualities needed to use the pen should not remain idle, should not bury his talents. Indeed, good journalism is an apostolate and, next to the priesthood, it is the most noble and sublime today.”